Two years ago, David Hazony -- founding editor of The Tower -- described the potential bond between Israeli Identity and the Future of American Jewry. He proposed that Israeli culture could energize the American Jewish community. A key part of this is Israeliness:

Today, on a patch of land dreamed about for millennia, millions of Jews are living a different Jewish life. And they are doing it in a way that continues to preserve identity across generations. And increasingly, that unique approach to life and history and identity are exporting themselves—their cultural products, their innovation, their very life essence—to America.But now it seems that Israeliness does not have to be exported in order to expand its impact.

In fact, the sense of identity offered by Israeliness may not even be limited to Jews.

In describing what he calls The Israelification of Israeli Arabs, Druze Israeli poet and essayist Salman Masalha points to a survey by Sicha Mekomit before the previous election. That survey found that

a deep process of Israelification is underway in Arab society. Forty-six percent of respondents defined themselves as Israeli Arabs, 22 percent as Arabs, 19 percent as Israeli Palestinians and only 14 percent as Palestinians. In other words, 65 percent affixed the term “Israeli” to the way they define themselves.Masalha wrote his article for Haaretz.

Contrary to prevailing conceptions, it turns out that the Arab public yearns to participate in determining the political and social agenda of this country.

Another writer for Haaretz, Alexander Yakobson, continues that thought that Arab citizens seek ‘Israeliness’ and goes further, quoting from other findings from that same survey that Masalha didn't mention.

For instance:

76 percent of Arabs say relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel in everyday life are “mostly positive” and only 18 percent described them as negative (compared to 53 percent and 33 percent, respectively, among the Jewish respondents). And 94 percent of the Arabs surveyed agree there is a Jewish people as well as a Palestinian people (while 52 percent of the Jews surveyed said there is a Palestinian people and not just a Jewish people). [emphasis added]This sense of Israeliness does not negate a Palestinian Arab identity.

Yakobson admits the need to be careful when evaluating surveys, especially when dealing with a single, individual one. After all, a lot depends on the way questions are phrased, and there are other surveys where the sense of a Palestinian identity is expressed more strongly. But despite those reservations, Yakobson believes the overall picture described by the survey Masalha cites does in fact correspond with dozens of surveys over the years.

He believes he can reconcile these 2 sides of an Arab identification with Israel while maintaining a Palestinian Arab identity as well:

My conjecture is that the Arab public votes as it does, first and foremost, because most of them accept the Palestinian national narrative that the Arab parties represent. However, in its attitude toward the state, most of this public does not draw the natural emotional conclusions from this narrative.The implication is that there is a sense of pragmatism at work here.

Sure, there are good pragmatic reasons for Arabs to prefer living in an Israeli state rather than a Palestinian one, but Yakobson another poll, the 2018 Israeli Democracy Index, according to which 51 percent of the Arab respondents went so far as to say they are "proud to be an Israeli."

That is more than just pragmatism.

He concludes that on the one hand the Arabs accept the Palestinian narrative and will continue to vote for those who promote it, while at the same time these same Arabs do not represent what that Palestine narrative implies.

While, neither the Arab nor the Israeli leadership can make claim to total allegiance from the Israeli Arab population, the Israeli government has an opportunity "to make it easier for the majority of Arab citizens to realize their desire to integrate more fully into Israeliness without forgoing their distinct identity."

That is good news when it comes to the Arab Israelis.

But what about the Palestinian Arabs?

On that score, David Goldman suggests that The Palestinian Problem Is Dying of Natural Causes -- literally -- on account of the failure of the oft-threatened "demographic bomb" to go off, as predicted by those who advised Israel of the urgency of making peace before Jewish Israelis become a minority in their own country.

Instead, the opposite was true.

Goldman quotes an article he wrote for the Asia Times, where he suggested that instead of making peace with a Palestinian Arab population "heavily tilted towards hot-headed youngsters", Israel should instead wait and take advantage of the declining Palestinian fertility rate which would raise the average age of the West Bank population. Comparable to the situation in Northern Ireland, the militants "would find themselves married with mortgages."

As proof of that potential for integration and peace, Goldman writes about the 5,800 Palestinian Arabs working at technology companies on the West Bank. He describes the booming Israeli software sector outsourcing to the West Bank, with Palestinian software companies filling orders for Israeli firms. Ariel University, located in Samaria, is a the top school for Palestinian computer science students and he brings quotes of the positive experience of Arab students who find that politics and academic studies can be separated.

Combined with Masalha and Yakobson the picture Goldman paints of the potential for peace is an encouraging one -- let's just hope that it is more successful than last time.

Last time?

An article last month in Haaretz describes the time When Arabs Were Invited to Live the Zionist Dream. The program was called Pioneer Arab Youth:

Young Arabs, mostly boys, from the country’s north were invited to live, study and work on kibbutzim. They left their village homes alone and spent years in these communities – working, eating and sleeping alongside the Jewish kibbutzniks. In some cases they made the move with their family’s blessing, but others were rebelling against their parents and their society.

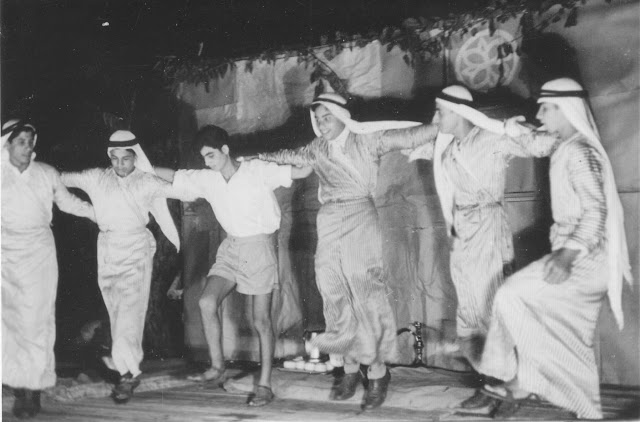

The Arab Pioneers learned Hebrew, danced the hora, raised the Israeli flag, sang “Hatikva,” the national anthem, and in some cases even took Hebrew names. Some began relationships with Jewish girls and aspired to assimilate into the kibbutz society. Others wanted to learn new agricultural methods with the aim of returning home and improving life in their villages. A few of them tried to realize a dream and establish an Arab kibbutz.

“The Jews we had met until then were part of the cruel suppression by the military government,” Mahmoud Younes recalls in a conversation at his elegant home in the town of Arara in the Triangle’s Wadi Ara area. Sitting next to an expressive painting of a dove of peace, he continues, “Suddenly we were sitting with Jews as equals. Eating with them in the [communal] dining room, working. A different Israel.”

The movement, which was an initiative of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair youth movement, existed from 1951 until 1966, the same year that military rule over the country’s Arabs ended. At its height, around 1960, it had 1,800 members and 45 branches in Arab villages. The participants had a uniform – the standard dark blue Hashomer Hatzair shirt with a white string, along with a kaffiyeh and aqal (headband). They also had their own emblem, in the form of a proud youth movement member standing under an Arab-style arch, and they had a variation of the movement’s slogan: “hazak vene’eman” – be strong and loyal – instead of “hazak ve’amatz” – be strong and brave. The Arab movement members took part in hikes, in May Day parades, even in Independence Day folk dancing.

|

| Members of the Pioneer Arab Youth movement, 1956. Credit: Hashomer Hatzair Archive |

|

| Jews and Arab youths dancing the debka on Kibbutz Yakum near Netanya, 1955. Hashomer Hatzair Archive / Yad Yaari Research & Documentation Center |

he had taught his wards about the fate of the Jewish people and their need for a state, and at the time saw no contradiction between the national aspirations of the Jews and the Arabs. “The intention was to educate for positive Arab nationalism, not aggressive nationalism that would turn against Zionism, but one espousing historical and literary values.”Some of the members took what they learned on the kibbutz and brought that know-how back to their Arab villages:

o In 1956, a cooperative vegetable garden called “The Pioneer” was founded in Kafr Yasif.According to historian Shaul Paz, the leaders of Hashomer Hatzair “wanted to believe that, just as a new Jew was being created, so, too, a new Arab would be created, one who could be a socialist, a pioneer and a kibbutznik as well.

o In Taibeh, an agricultural cooperative called “The Hope” was established. It included a plan for setting up a cooperative movie theater, that never came to fruition.

o In 1957, a water-drilling project that Younes established in Arara.

But in the end, despite the original promise and success, there was disillusionment.

According to one former member of the Pioneer Arab Youth:

“the coexistence was forced, not genuine. Coexistence is expressed in everyday life, in deeds, not in theories. It was hypocrisy per se, and I think that the same hypocrisy exists to this day. The kibbutzim believe above all that this is a Jewish state and that the Jews in it are more privileged than the Arabs and have priority in everything.Though the Arabs interviewed did not see it, it may be, if the surveys are accurate, progress has been made since then.

Maybe in part because of the demographics that Goldman refers to.

Maybe it is a function of time -- and realizing that neither the Arabs nor the Jews are going anywhere.

At least it is a start.

We have lots of ideas, but we need more resources to be even more effective. Please donate today to help get the message out and to help defend Israel.

Elder of Ziyon

Elder of Ziyon

![[Elder of Ziyon] Facebook may add "Insha'Allah" button for events](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi9KIDYyRBYSDMD-x2PZwXZNYKl0eHCeNWbuEWt6IvsNL6IFhtZTpF2SvNRlui4o-nPTjPMcmSOxJ1nPo0pPGPzI5r7GHO_ZfKV9WUcNnkMeMslnkgWq0GeILJg-5vXLLCLckj6SUmdJqmc/s72-c/arabic_facebook_logo_by_ali_normal-d37tr0q.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment